The History of Boost Governance

Great Founder Theory in C++

The History of Boost Governance: From Beman Dawes to the Stewardship Crisis

Abstract

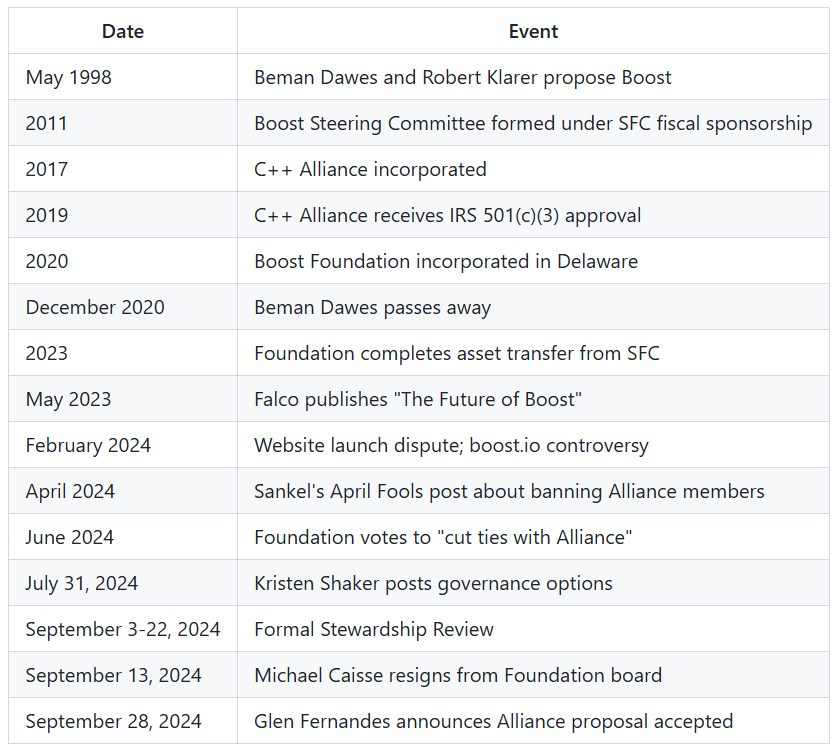

This paper tells the story of Boost governance from its founding in 1998 through the 2024 governance crisis and its resolution. We trace the project’s evolution from its origins under Beman Dawes, through fiscal sponsorship with the Software Freedom Conservancy, to the formation of the Boost Foundation and the rise of the C++ Alliance. We examine the 2024 governance crisis that presented the community with two competing visions, the formal review process that resolved it, and use Great Founder Theory to understand the dynamics at play. We conclude with projections for Boost’s future under the Alliance governance model versus a counterfactual Foundation-controlled trajectory.

Introduction

This paper tells the story of how the Boost C++ Libraries evolved from a volunteer-driven project into a community facing a governance crisis. Since 1998, Boost has served as both a proving ground for innovations that would later enter the C++ Standard Library and as a collection of production-quality libraries used by millions of developers worldwide. The governance of this project—how decisions are made, who controls assets, and who sets direction—has proven as complex and consequential as the technical challenges the libraries address.

This is a story about people trying to do the right thing for Boost, with different ideas about what that means. The 2024 crisis forced the community to choose between two fundamentally different visions for its future. We’ll trace how this came about through historical precedent, communication patterns, and the formal review process that resolved it.

To understand what happened, we’ll use Samo Burja’s Great Founder Theory as a lens. This framework suggests that functional institutions are rare, and that when exceptional founders (like Beman Dawes) create them, succession becomes the critical challenge. When founders depart, institutions often struggle to maintain their original effectiveness. This isn’t about heroes and villains—it’s about how institutions work, and what happens when the people who built them are no longer there.

The Founding Era: Beman Dawes and the Original Vision

The 1998 Proposal

Boost began with a proposal from Beman Dawes and Robert Klarer in May 1998 for a website offering curated, high-quality C++ libraries. The founding document evokes what would become a transformative movement in C++ development:

“The outcome is a collection of posts where each reviewer summarizes their critique of the library, including whether or not to ‘accept’ the library (sometimes with conditions).”

This description of the Formal Review process established the social technology that would define Boost for decades. Unlike other open-source projects that relied on informal maintainer approval or corporate sponsorship, Boost created a peer-review system modeled loosely on academic publishing—rigorous, transparent, and community-driven.

The Boost Software License

The second foundational innovation was the Boost Software License (BSL), designed to eliminate the license compatibility conflicts that plagued other open-source ecosystems. The BSL’s permissive terms allowed Boost code to be incorporated into both open-source and proprietary projects without friction, creating powerful network effects that accelerated adoption.

Beman Dawes as Great Founder

Beman Dawes fits the pattern of what Great Founder Theory calls a “great founder”—someone who creates social technologies that enable sustained coordination. Dawes didn’t merely contribute code; he created the systems and processes that enabled hundreds of volunteers to collaborate effectively across decades.

Dawes’ contributions included:

The formal review process

The Boost Software License

Serving on WG21 and chairing the Library Working Group

Personally managing key infrastructure including the boost.org domain

As Vinnie Falco noted in his 2023 “Future of Boost” essay:

“Beman was the closest thing resembling a leader, despite Boost being a federation of authors with each having final word over their own library. Beman would solve problems, help with the direction of things, and even ‘beat the bushes’ when it was time for a review by reaching out to his network of contacts and soliciting their participation. Without Beman, Boost lost its leader. Boost lost its Great Founder. And no one has since filled the role.”

The Software Freedom Conservancy Model

Fiscal Sponsorship Before the Foundation

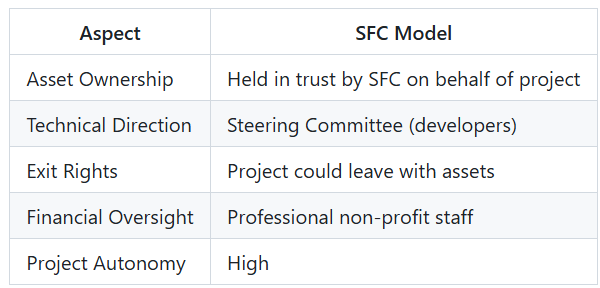

Before the Boost Foundation existed, the project operated under fiscal sponsorship with the Software Freedom Conservancy (SFC). This arrangement, established through Beman Dawes’ efforts, provided:

501(c)(3) non-profit status for tax-deductible donations

Financial oversight and accounting

Legal protection for the project

Critically, the SFC model was governed by a Fiscal Sponsorship Agreement (FSA) that included explicit provisions:

“The Steering Committee determine the technical, artistic, and philanthropic direction of Boost.”

This language ensured that while the SFC held assets in trust for legal and financial purposes, governance authority remained with the developers through the Boost Steering Committee. The FSA created a clear separation between fiscal responsibility (SFC) and project control (developers).

Critically, the FSA included exit rights—the project could leave with its assets if the relationship didn’t work. This provision would become important later, as it established the principle that fiscal sponsorship means stewardship, not ownership.

Key Characteristics

This model worked for over a decade because it aligned incentives correctly: the SFC had no interest in controlling Boost’s technical direction, and Boost had professional financial management without surrendering sovereignty.

The Rise of the C++ Alliance

Vinnie Falco’s Vision

The C++ Alliance was incorporated as a California-registered 501(c)(3) non-profit in 2017 (receiving IRS approval in 2019). Its founder, Vinnie Falco, conceived the organization as a vehicle to support C++ development through charitable donations:

“I despise paying taxes. In 2017, I had an idea: create a charitable organization which I can donate pre-tax income to, and then I could hire Christopher Kohlhoff as a ‘staff engineer’ to work full time on C++ standardization, and Boost things!”

While this origin story emphasizes tax efficiency, the Alliance’s mission expanded to encompass a broader vision for C++ and Boost:

Employ full-time Staff Engineers to contribute to open-source C++

Provide infrastructure (CI, hosting, build systems)

Create documentation and educational resources

Market and promote Boost to new audiences

Alliance Contributions to Boost

By 2024, the C++ Alliance had made substantial investments in Boost infrastructure:

Infrastructure:

Deployed Drone CI when Travis discontinued free service

Sponsored Fastly CDN for release archive downloads

Provided GitHub Actions self-hosted runners

Assisted with wowbagger server administration

Library Development:

Boost.Beast (HTTP/WebSocket)

Boost.JSON

Boost.URL

Boost.MySQL development and maintenance

Boost.Unordered optimization

Boost.Charconv development

Marketing and Outreach:

New website development

CppCon promotional materials

Twitter/X account management

Full-time Senior Technical Writer

Falco’s Leadership Style

Falco’s approach to Boost reflected what John Maddock characterized as the “move fast and break stuff” school of working. This manifested in:

Rapid development of new infrastructure

Willingness to deploy changes before full consensus

Direct engagement with criticism on mailing lists

Personal funding of initiatives without formal approval processes

This style created tension with the more consensus-driven traditional Boost culture, but also produced tangible results that many community members valued.

The Foundation Era: Centralization and Community Response

Formation and Transition

In 2020, Jon Kalb created the Boost Foundation as a Delaware-registered 501(c)(3) non-profit organization. The Foundation was intended to assume stewardship of Boost’s assets from the Software Freedom Conservancy and provide more direct community control.

The transition was completed in 2023 when funds were fully transferred from the SFC to the Foundation. However, an important difference existed between the two arrangements: unlike the SFC model, the Foundation didn’t establish a Fiscal Sponsorship Agreement with explicit exit rights. The Foundation assumed direct ownership of Boost’s assets without contractual obligations to the developer community.

Organizational Structure

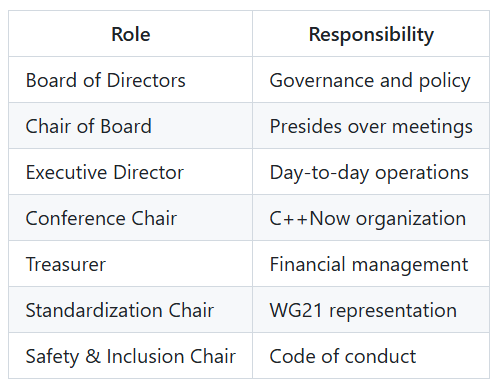

The Foundation’s structure included:

The Foundation also assumed responsibility for the C++Now conference, WG21 standardization representation, and various infrastructure projects.

David Sankel’s Leadership

David Sankel emerged as the central figure in the Boost Foundation through his roles as Chair of the Board and Executive Director. As a Principal Scientist at Adobe and an active member of WG21, Sankel brought significant technical credentials to the role. His vision was to provide stable governance for Boost.

However, David Sankel’s approach centralized decision-making within the Foundation. The Foundation’s minutes reveal a pattern where decisions occurred primarily within board meetings rather than through mailing list consensus:

Board elections occurred at annual C++Now meetings without mailing list participation

New board members were nominated through private processes

Key decisions about infrastructure and relationships were made in closed sessions

Sankel’s approach reflected his view that centralized control was necessary for effective governance, though this created tension with Boost’s traditional consensus-driven culture. His dual role as both Chair of the Board and Executive Director concentrated power unusually, and his pattern of announcing ambitious plans without demonstrated implementation capacity would become a recurring issue.

The CMake Initiative: A Preview of Governance Dynamics

Years before the 2024 crisis, the Steering Committee—including David Sankel—provided a preview of its governance philosophy in the 2017 CMake discussion. In July 2017, Jon Kalb, as Steering Committee Chair, announced the committee’s “desire and intent to move Boost’s build system to CMake”:

“In a similar vein our build system has become an impediment for many developers and users, existing and prospective. Therefore, we, the Steering Committee, announce to the Boost community our desire and intent to move Boost’s build system to CMake for users and developers alike.”

This followed David Sankel’s June 2017 proposal outlining a migration path that would culminate in “Remove Boost.Build entirely.”

The announcement generated significant resistance, with community members objecting not primarily to CMake itself, but to the top-down governance approach.

Stefan Seefeld (Boost.Python maintainer) articulated the core objection:

“The problem isn’t a technical one, it’s systemic / organisational.”

“What we need is for project maintainers to be able to pick tools they understand so they can operate more autonomously. It shouldn’t be for any central Boost authority to decide top-down what is best for all projects!“

Robert Ramey expressed skepticism of centralized planning:

“More central control sounds like a good idea, but it results in decisions driven more by politics, particular conflicting interests, excessive conservatism by bureaucrats and other entrenched interests.”

His alternative approach was prophetic:

“Encourage library authors to include CMakeLists.txt files in their directories. If some committee wants to complain about it, we’ll deal with it then.”

“If CMake is successful, boost build would die on its own. If you have to forcibly remove it, you’ve failed.“

When pressed on implementation, David Sankel offered an optimistic response that would prove characteristic of his leadership style:

“Once we decide on a direction, I don’t foresee a problem making this happen. Between volunteers, the importance this project has for companies, and the Steering Committee reserves, we should have the resources necessary.”

Robert Ramey’s sardonic reply captured a broader concern:

“LOL - promote this guy to management !!!!”

Outcome: The Steering Committee’s mandated CMake transition didn’t proceed as planned. Instead:

Boost.Build (b2) remains the officially supported build system for releases

CMake support grew organically, library-by-library

Peter Dimov—notably, someone who would later become a Foundation board member but a vocal critic of its direction—quietly built the actual CMake infrastructure that works

The boostorg/cmake repository provides CMake support through volunteer effort, not committee mandate

This outcome validated Ramey’s prediction: useful tooling adopted bottom-up succeeds; top-down mandates struggle. The community found its own path forward.

The CMake episode demonstrated a pattern that would recur: David Sankel and the Foundation favored top-down mandates, while the community preferred maintainer autonomy. When the Foundation later promised to “complete the CMake migration” in its 2024 governance proposal, community members had reason for skepticism based on this experience. The 2017 episode showed that Sankel’s announcements often lacked follow-through, while actual progress came from individual contributors working without mandates.

The Beman Project

In 2024, the Foundation launched the Beman Project, described in their minutes as:

“A new initiative separate from Boost that gets back to its original purpose of improvements to the standard library.”

This project prompted questions within the Boost community:

Licensing: The Beman Project used the Apache license with LLVM extensions rather than BSL, which would complicate integration with Boost

Expanded Scope: Foundation resources were being directed to a project separate from Boost itself

Lack of Transparency: The project was conceived and launched without mailing list discussion

As Ion Gaztañaga noted in his formal review:

“It gives me a bittersweet feeling... The fact that the recommended license for that project is not BSL is also disappointing.”

Peter Dimov’s observation:

“I think that the primary purpose of an entity named ‘the Boost Foundation’ should be to support Boost, and if it currently isn’t, something not quite right.”

While well-intentioned, this created some uncertainty about Foundation priorities.

The June 2024 Decision

The Foundation’s June 2024 meeting, with only four members present, voted to:

“Procure alternative sources of funding to replace all C++ Alliance funded things and to abstain from future involvement with the C++ Alliance.”

This decision, made without broad community input, exemplified the governance concerns that would fuel the crisis.

The 2024 Governance Crisis and Resolution

The Domain Controversy

The crisis crystallized around the boost.org domain name. After Beman Dawes’ death in December 2020, the domain remained in his estate. The Foundation attempted to acquire it, but discovered the C++ Alliance had independently approached the Dawes estate:

From the Foundation’s June 2024 minutes:

“The C++ Alliance attempted to buy the boost.org domain name from Beman Dawes’s widow. We, by chance, got in contact with her and knowing the situation no longer plans to move forward. She was unaware of our existence, but was happy that we reached out because she was about to sign the documents.”

The Foundation characterized this as a “secret attempt” that demonstrated the Alliance’s desire to “bypass the Board in all future decision making processes.”

The boost.io Website and Escalating Tensions

The Alliance had developed a complete new website for Boost at boost.io while negotiations with the Foundation stalled. David Sankel’s response on February 23, 2024 became one of the most heated communications of the crisis:

“I’m sorry Vinnie, but I don’t think you understand the extent of the broken trust between you and the board. It’s too bad. I thought you had a good thing going, but you messed it up.

You want to own boost.org, you want to own the boost website, you want to own the boost logo, and you want to own the boost mailing list. The answer is no, no, no, and no. If you decide to close shop and spend your money elsewhere, Boost will go on just fine. I’m committed to make sure that will always be the case, not just for you but for any single individual. Boost is not for sale.

boost.io is an illegitimate imposter boost.org site and should be taken down.”

David Sankel’s communications during the crisis took a protective stance, reflecting his view that the Foundation needed to defend Boost from what he perceived as a competing vision. His messages were often defensive and accusatory, characterizing Alliance actions as “hostile takeover attempts.” He acknowledged his own struggles with the situation:

“I’ve lost my cool when I’ve perceived hostile takeovers and attacks on the Boost Foundation, sending out emails embarrassing everyone involved.”

Sankel’s April Fools post, while ostensibly a joke, revealed genuine sentiments the Foundation had discussed internally—including banning Alliance members and removing their libraries. This pattern of inflammatory communication, combined with his tendency to make decisions without broad community input, contributed to the governance concerns that fueled the crisis.

Falco’s communications, by contrast, were more solution-oriented:

“Louis already conveyed that his communications might not have been clear, so we are willing to concede this point to you. That said, our position is explained now and the website is almost ready to be published so for the third time we are asking, how can we make the best of the work that we have done and figure out a mutually agreeable solution?”

Falco frequently cited specific contributions and actions, and maintained a collaborative tone:

“I don’t want to ‘control Boost.’ Instead, I’d like to help make Boost even better. Please join me in this effort.”

This was a complex situation with valid perspectives on all sides. Different people had different ideas about what was best for Boost.

The Community Choice

On July 31, 2024, Kristen Shaker, as Board Chair, posted a formal letter to the mailing list presenting the community with two options:

“The C++ Alliance and the Boost Board of Directors have had their disagreements. Recently, it has become apparent - in particular via their attempt to purchase the boost.org domain name and the proposed new Boost Logo - that The Alliance would like to exert a greater sense of ownership over Boost Library assets.

While the C++ Alliance is a non profit organization, it is wholly funded and effectively controlled by one individual - Mr. Falco. The Board of Directors has a stewardship responsibility to Boost and we are wary of a single individual exerting such a level of control over the Boost Libraries.”

The letter presented two options:

Option 1: The C++ Alliance assumes control of Boost assets; Foundation becomes uninvolved

Option 2: The Foundation continues as steward; Alliance-developed assets transfer to Foundation

The Competing Proposals

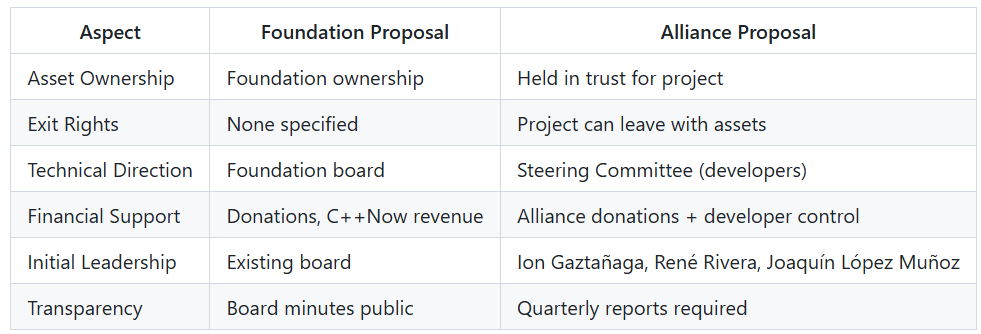

The Foundation Proposal emphasized community values like transparency, consensus building, and volunteerism. The Foundation proposal retained ownership of Boost’s assets with no exit mechanism for the project.

The Alliance Proposal explicitly modeled itself on the original SFC arrangement:

Alliance becomes fiscal sponsor

New Steering Committee composed of Boost developers

Assets held by Alliance on behalf of project

Contractual agreement governing relationship

The critical distinction: The Alliance proposal included exit rights—the project could leave with its assets if the relationship didn’t work. This restored the principle that had existed under the SFC model.

The Formal Review

Glen Fernandes, serving as a neutral arbiter despite being a Foundation board member, announced the Boost Asset Stewardship Review for September 3-22, 2024. The review followed Boost’s traditional formal review process, adapted for a governance decision rather than a library acceptance.

John Maddock (Vote: Alliance):

“There are strengths and weaknesses on all sides, but as things stand, I vote to move control of boost.org’s assets to the C++ Alliance. To me it seems like the balance of risks is lower on that side, but also we gain the support of a group of people who are not only already committed to Boost, but also committed to injecting more energy and involvement in the project.”

Ion Gaztañaga (Vote: Alliance with conditions):

“I’m a bit puzzled that after that first attempt or when Boost domain registration problem happened the community was not informed that the Foundation was not the real owner of the domain.”

“I’m happy that the current proposal addresses a major concern expressed by the Boost Foundation... the risk of ‘a single individual exerting such a level of control over the Boost Libraries.’ Precisely the SC + fiscal sponsor proposal addresses this concern, because it is not the C++ Alliance who will establish Boost’s direction but the SC.”

The Outcome

On September 28, 2024, Glen Fernandes announced the result:

“On behalf of the Boost community, I accept the C++ Alliance Fiscal Sponsorship proposal with the following condition:

The new committee should be named something which clearly indicates that its purpose is confined to Boost’s assets or infrastructure. There should be no confusion or question over whether it has any control or even other influence over the C++ library development. Please avoid any mention of ‘Steering’ or ‘Direction.’

I accept the three initial members of the committee as proposed (Ion, Rene, Joaquin) without reservations.”

Fernandes’ statement acknowledged the community dynamics:

“It has the support of a great majority of the Boost community. It is no secret that there has been a growing rift between the Boost developers and some of the Foundation members, despite my and others best attempts at healing it.”

Remarkably, Fernandes also stated:

“I would also like to make it known that I will submit a suggestion in the next meeting that the Boost Foundation rename itself to not include the word ‘Boost.’“

Shortly after the review announcement, Michael Caisse resigned from the Foundation board on September 13, 2024, signaling the fracturing of the Foundation’s position.

Understanding What Happened: Great Founder Theory and Governance Models

The Framework

Great Founder Theory helps us understand what happened with Boost. The framework suggests that:

Functional institutions are the exception, not the norm—most organizations merely imitate functional ones

Great founders create social technologies that enable sustained coordination

Succession is the critical challenge—when founders depart, institutions typically decay

Institutions without great founders become “photocopies of photocopies,” losing fidelity with each generation

This framework helps us understand what happened, not to assign blame. It’s about how institutions work.

Beman Dawes and the Succession Challenge

Dawes created Boost’s essential social technologies:

The Formal Review (peer validation)

The Boost Software License (legal framework)

The federated author model (distributed ownership)

The mailing list culture (transparent deliberation)

These innovations weren’t obvious or inevitable—they required exceptional judgment about what would enable long-term collaboration among volunteers.

When Dawes died in December 2020, Boost entered the succession crisis that Great Founder Theory predicts. The project had:

No designated successor

No mechanism for selecting one

Declining participation metrics

Aging infrastructure

The Foundation attempted to fill this vacuum through formal structure, but structure without the founder’s knowledge and judgment can produce what Burja calls “non-functional institutions”—organizations that imitate the form of leadership without the substance.

The 2017 CMake episode exemplified this dynamic. David Sankel and the Steering Committee announced grand plans but lacked the capacity to execute them. The actual CMake infrastructure that eventually worked was built organically by Peter Dimov—not through committee mandate, but through individual initiative. This pattern of announcing without delivering would characterize Sankel’s leadership approach.

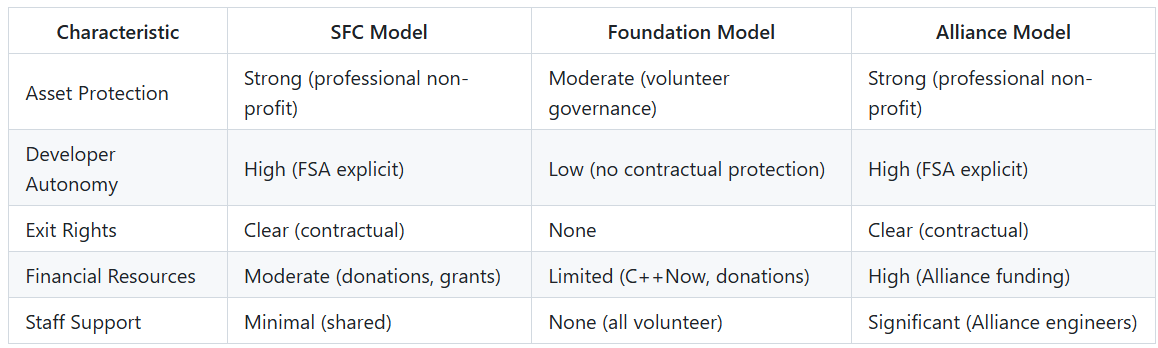

Two Competing Approaches

The Foundation represented formalization—attempting to institutionalize governance through structure, process, and bureaucracy. This approach produces legibility at the cost of effectiveness.

The Alliance represented refounding—an attempt by a new founder figure (Falco) to inject the energy, resources, and vision that characterized early Boost. This approach trades institutional stability for dynamic growth.

Comparing the Governance Models

The Exit Rights Distinction

When Jon Kalb transferred assets from the SFC to the Foundation, the contractual protections that had safeguarded developer control were not replicated. The Foundation’s proposal didn’t include exit rights.

The Alliance proposal explicitly restored these protections:

“The proposed FSA includes provisions allowing the Steering Committee to transfer the project to a new sponsor if necessary.”

This single provision represents the difference between stewardship (holding assets on behalf of beneficiaries) and ownership (holding assets as one’s own property). The community preferred a model that preserved the right to leave if the relationship didn’t work.

Forward-Looking Projections

Boost Under Alliance Governance (10-Year Projection)

Based on the Alliance’s track record and stated intentions:

Infrastructure (Years 1-3):

Modern website at boost.org

Upgraded mailing list (Mailman 3)

Cloud-based infrastructure replacing wowbagger

Expanded CI resources

Community (Years 3-5):

New documentation tooling (MrDocs replacing Doxygen)

Improved onboarding for contributors

Regular promotional presence at conferences

Active social media engagement

Libraries (Years 5-10):

Continued Alliance-funded library development

Potential new review participants attracted by modernization

Possible stabilization of declining participation metrics

Risks:

Dependence on Falco’s continued engagement and funding

Potential conflicts between Alliance priorities and community preferences

Governance challenges if Falco’s vision diverges from Steering Committee

Likely Outcome: Boost appears likely to stabilize and potentially experience modest growth. The project becomes more professional in presentation while maintaining its technical standards. The Alliance’s resources address infrastructure debt. Whether the core challenge—declining participation in formal reviews—is solved remains uncertain, as this requires cultural shifts beyond infrastructure investment.

Counterfactual: Boost Under Foundation Governance (10-Year Projection)

Had the Foundation retained stewardship, the path might have looked different:

Infrastructure (Years 1-3):

Continued reliance on aging wowbagger server

Challenges replacing Alliance-funded infrastructure

Possible service disruptions as volunteer resources might prove insufficient

Community (Years 3-5):

Possible continued decline in mailing list participation

Increasing age of active contributor base

Potential disconnect between Foundation board and developers

Libraries (Years 5-10):

Possible ongoing decline in formal review activity

Potential departures of Alliance-affiliated maintainers

Risk of libraries becoming increasingly unmaintained

The Beman Project:

Foundation resources directed to a separate project

Potential confusion about Boost vs. Beman identity

Possible community fragmentation

Risks:

Insufficient resources for infrastructure

Volunteer burnout without organizational support

Risk of declining relevance as C++ ecosystem evolves

Likely Outcome: The Foundation’s limited resources and volunteer model might have proven insufficient to address accumulated technical and social debt. The Beman Project could have created organizational confusion. Boost might have become more of a legacy project—still used but no longer growing or attracting new libraries. However, this is speculative; the community chose a different path.

Conclusion

The history of Boost governance demonstrates the challenges inherent in sustaining volunteer-driven technical communities across leadership transitions. Beman Dawes’ creation of Boost was an act of institutional founding that produced social technologies—the Formal Review, the BSL, the mailing list culture—that enabled remarkable success for over two decades.

His death created a succession crisis. The Boost Foundation struggled with this transition. The Foundation’s approach of assuming ownership without contractual protections for developer control represented a different understanding of stewardship than the community preferred—one that the community ultimately rejected. The Beman Project, while well-intentioned, created uncertainty about Foundation priorities.

David Sankel’s centralization of decision-making, though intended to provide stable governance, created significant tension with Boost’s traditional consensus-driven culture. His pattern of announcing ambitious plans without demonstrated implementation capacity, his tendency to make decisions in closed sessions without mailing list participation, and his inflammatory communications during the crisis all contributed to the community’s loss of confidence in Foundation leadership. Sankel’s dual role as both Chair and Executive Director concentrated power unusually, and his approach of defending positional authority rather than building consensus ultimately alienated the developer community.

The C++ Alliance, for all the controversy around Vinnie Falco’s rapid-development approach, offered something the Foundation could not: resources, energy, and a governance model that respected developer autonomy. The Alliance proposal’s explicit exit rights—the right for Boost to leave if the relationship doesn’t work—was the decisive factor. This provision demonstrated understanding that stewardship is service, not ownership.

The September 2024 Formal Review, in which a “great majority” of the community accepted the Alliance proposal, represented a collective judgment that:

The community chose a different path from the Foundation’s model

The Alliance’s contributions merited trust

Developer control must be contractually protected

Exit rights are essential to legitimate governance

As Glen Fernandes noted, he would suggest the Foundation “rename itself to not include the word ‘Boost.’” This recommendation acknowledged that from the community’s perspective, the Foundation’s model no longer aligned with Boost’s needs.

Looking forward, the Alliance model offers promise for Boost’s stabilization and potential renewal. The combination of professional infrastructure, funded development, and contractual developer autonomy addresses the project’s most pressing challenges. Whether this proves sufficient to reverse decades of declining participation remains to be seen—only time will tell. But it represents a path the community was willing to try.

The Boost governance crisis, viewed through Great Founder Theory, illustrates both the fragility of institutions after founders depart and the possibility of refounding through new leadership. Vinnie Falco may not replace Beman Dawes, but his Alliance has provided the resources and framework for Boost’s next chapter. The community’s acceptance of this arrangement—conditional, watchful, but ultimately affirmative—represents hope that Boost’s best work may still lie ahead. The future remains to be written.

References

Primary Sources

Boost Foundation Board Minutes (2020-2024)

C++ Alliance Fiscal Sponsorship Proposal (2024)

Boost Foundation Stewardship Proposal (2024)

Boost Developers Mailing List Archives (2023-2024)

Secondary Sources

Falco, V. “The Future of Boost.” C++ Alliance Blog, May 8, 2023.

Shaker, K. “A Follow Up to My Original Note Re The Future of Boost.” Boost Mailing List, July 31, 2024.

Fernandes, G. “Boost Asset Stewardship Review Result.” Boost Mailing List, September 28, 2024.

Theoretical Framework

Burja, S. Great Founder Theory. 2020 Manuscript.